Veteran Mr Colin Wagener shares his WWII story

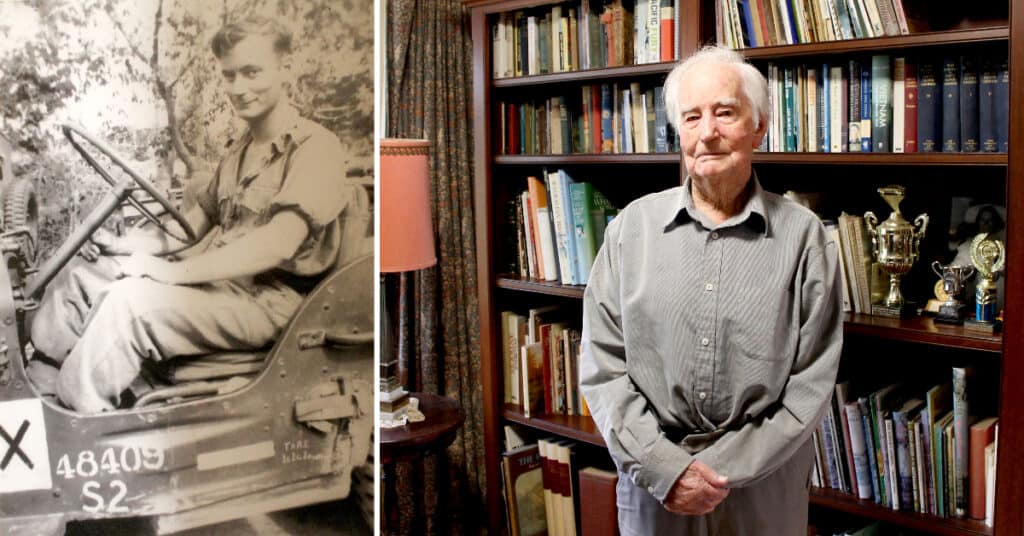

When Mr Colin Wagener, now aged 105, joined the army in 1938, he had no idea that he would photograph one of the most historic events of WWII.

Mr Wagener signed up to join the militia forces part-time at Keswick Barracks in 1938, with his three best friends. Sadly, he would be the only one of the four to survive the war.

‘For the first part of my army life, I was stationed in Woodside, working in signals intelligence. I had always been interested in radios and knew what I was doing with them.’

‘In 1939, I joined the army full-time. I was posted to Loveday to establish a radio connection between Adelaide and Darwin.’

‘I worked well in that role so, in 1942, when things were getting more serious, I received notice that I would be posted to the army camp at Bonegilla in Victoria to work as an instructor.’

He only had about four hours’ notice before he was due to leave, so he rushed back to Adelaide to marry his sweetheart, Peggy. He says, ‘It wasn’t very romantic. We quickly married in the registry office in the city, and then I immediately headed to Bonegilla.’

‘While I was there, I worked my way up in the ranks —Lance Corporal, to Corporal, to Sergeant.’

In 1944, Mr Wagener had to move locations once again, this time to work in the signal office in Townsville.

‘I worked in Townsville for a while, and then in 1945, the Air Regiment gave me my own operational unit.’

‘We travelled on an LST [Landing Ship Tank] to Morotai, Indonesia. We saw other LSTs come in and knew we would be part of a convoy, but we didn’t know where we would be going. We weren’t told until we were at sea that we were headed for Borneo.’

‘We had a beach landing in Borneo and took the island back from the Japanese. It was only after we reclaimed the territory that we discovered the enormous atrocities committed, including the Sandakan Death Marches.’

‘We were after the war criminals who did it, and Japanese General Baba Masao was at the top of our wanted list.’

‘After Japan surrendered, General Baba arrived via plane at Labuan Airstrip to sign the surrender document. The red roundels on his plane were marked with white crosses, a sign of humiliation.’

‘I had my camera with me, and I just knew that I had to capture this moment of history.’

‘Unbeknownst to me at the time, there was an official war photographer also there to document the historic occasion.’

‘I photographed as much of General Baba’s surrender as I could and also took photos of other war criminals we had captured.’

‘It was lucky that I wasn’t a smoker, as I traded in all my rationed cigarettes for photography darkroom equipment.’

‘I didn’t need an official darkroom — the dark night sky was it! I developed the photos at night.’

For a few months after the surrender, Mr Wagener and his fellow troops remained in Borneo, scheduled to go home on 10 December 1945.

‘Our homecoming was called “Operation Santa,” as they wanted to ensure that we were all home for Christmas,’ says Mr Wagener.

On the morning of departure, Mr Wagener was trading cigarettes for more camera equipment when he heard a massive bang.

He explains, ‘While taxiing for take-off, a plane swung off course and crashed. We all ran to the site, but it was too late, the six Australian officers and crew aboard all died in the explosion.’

‘I photographed everything so that there was a record of what happened. Suddenly, I was grabbed by the shoulder, and everyone yelled, “It’s time to go! We’re going home!”’

To this day, the untimely accident is a prominent memory for Mr Wagener: ‘I just can’t get my head around it; those men survived the war, only to die in an accident afterwards,’ he says.

In mid-late December, the troops finally arrived back in Australia, docking in Brisbane.

‘To be honest, I thought everyone would’ve forgotten about us, as we arrived a few months after the war had ended. But it was the complete opposite,’ says Mr Wagener.

‘As we sailed down the Brisbane River, passing boats celebrated by shooting water from their firehoses high into the air. Once we docked, we were driven down the main street of Brisbane, and there was a full ticker-tape parade.’

‘We were wet, hungry, and tired, but we didn’t care — we were home.’

Eventually, Mr Wagener boarded a special troops train, which took him back to Adelaide.

‘The best Christmas present I ever received was at half past ten on Christmas morning, 1945. The train rolled into Adelaide station, and I was on it,’ he recounts.

‘My father picked me up and brought me home, and my wife and two sons were waiting for me.’

‘It was the most wonderful feeling to be with my family.’

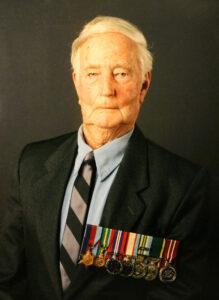

‘I was discharged after serving nearly 2,000 days in the army, and I was awarded the Australian Efficiency Medal. It was such an honour.’

‘But most importantly, considering everything our prisoners-of-war went through, I was so pleased that General Baba Masao was eventually brought to trial and punished for his war crimes.’

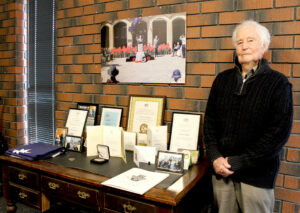

It wasn’t until the 50th Anniversary of the Second World War that Mr Wagener began to truly reflect on his time of service. He recovered his photographs and compared them with the ones taken by the official photographer.

‘I felt that the official photographs of the war did not represent was truly happened — I didn’t like how much of what I saw in real life was censored,’ explains Mr Wagener.

‘I suppose it was done to protect the prisoner-of-war families, but I felt that nowadays, people had a right to know what really happened back then.’

‘So, I contacted the Australian War Memorial and showed them my photographs to give another perspective of what happened. They now feature in the Australian War Memorial in Canberra, alongside the official photographs.’

In his later years, Mr Wagener enjoys a quiet life, remaining at home with his son on a property in the Adelaide Hills, and receiving services from Resthaven Murray Bridge, Hills & Fleurieu Community Services.

In his later years, Mr Wagener enjoys a quiet life, remaining at home with his son on a property in the Adelaide Hills, and receiving services from Resthaven Murray Bridge, Hills & Fleurieu Community Services.

Mr Wagener’s war time service was one of many millions that contributed to life as we know it today, and like all wartime experiences, his is unique.

Thank you for sharing your story, Mr Wagener!