Code-cracking during World War II

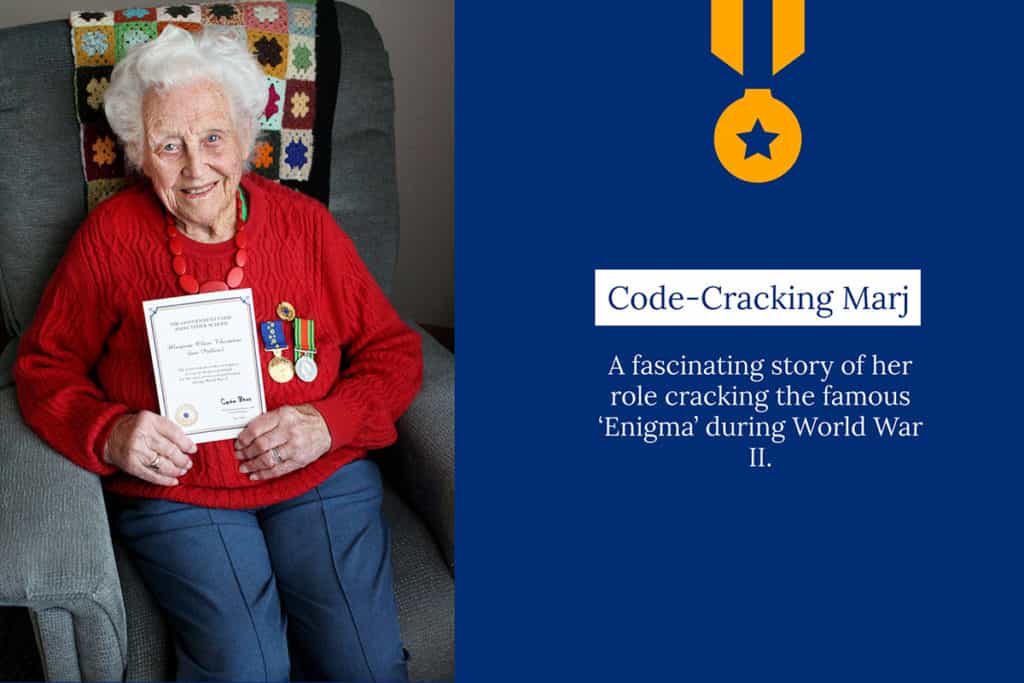

Code-cracking Marj

Mrs Marj Thornton (98) of Resthaven Port Elliot has many interesting stories—but one of the most fascinating is her role in cracking the famous ‘Enigma’ during World War II.

Born in Birmingham, England, in 1921, Marj says, ‘My story really begins in 1942. Birmingham was a large city in the heart of the industrial midlands. Like all other big cities, since the autumn of 1940, we had spent almost every night in our Anderson shelter in the back garden.’

She remembers evacuating twice in the middle of night – first for an unexploded land-mine close to the bottom of the garden, and next when another land-mine demolished a row of houses in the next street.

At age 20, Marj was conscripted. ‘You had three choices: munitions factory, land army, or services,’ she says. ‘l chose to go in the army, which was a tremendous culture shock.’

‘There was no privacy – we slept in large barracks with girls from every walk of life. I’d never before heard really offensive language (I’d never heard my father swear), or seen young ladies blind drunk.’

‘Luckily, they were not all like that, and I found a couple like myself.’

At the end of the month, Marj was asked to be a Wireless Operator (WOp), and ‘thought that sounded different, so I agreed.’

She was posted to Trowbridge on Salisbury Plain, and was one of the first girls to do the wireless training course. ‘The first thing I had to learn was dots and dashes, then earphones,’ she says.

‘I had to learn to take down Morse code at 25 words per minute, and learn numbers, punctuation marks, and international Q code, which was used by all signallers in every country to talk to each other.’

From Trowbridge, Marj was sent to an old country house, Shenley, where the group were introduced to the ‘Superhets’ wireless sets, given a frequency to cover, and told to take down everything they heard.

Marj explains, ‘This is where we learned what we were actually going to do, which was intercept messages from the German army under the Official Secrets Act.’

Just after Christmas 1942, Marj and her friend, Joy, were sent to Kedleston Hall. ‘We lived in Nissen Huts with 12 girls in a hut, working in six hour shifts. They would have a 15 minute coffee break halfway through, then 36 hours off. Talk about jet lag!’

Marj says, ‘At the time, we had no idea of what really went on at Bletchley Park, as the only information anyone working on Enigma was told was what they needed to know.’

‘The personnel at Bletchley Park were housed in different huts. For example, Hut 6 might receive initial messages to decipher. If they succeeded, the message was passed on to Hut 3, where it was translated. They then decided on the urgency of the message, and whether liaison with the War Office or Winston Churchill was necessary.’

‘In the very early days, deciphering had to be done manually. It involved miles of punched tape, which had to be matched up – a process similar to a huge slide rule. This was a long and painstaking business, and traffic had to be deciphered as quickly as possible or it would be out of date.’

‘Then they came up with a machine called bombe, which was 8 foot tall and 7 foot wide. Bombes unravelled wheel settings for enigma ciphers.’

‘The front were rows of coloured circular drums five inches in diameter, with the letters of the alphabet painted on the outside of each drum. The back of the machine was a mass of dangling plugs on rows of letters and numbers.’

‘Use of bombes meant that messages were deciphered in a much shorter time.’

‘There were several locations for these bombes in small villages in area, with ten or more in each room. Imagine the noise!’

‘However, more sophisticated, high speed machinery was needed. Colossus 1 was rolled out at the end of 1943, and Colossus Mark 2 was brought into commission on 2 June 1944.’

‘By 1945, Britain kept ten Colossi busy, decrypting 1,200 messages a month. By the end of the war, they had decrypted 63 million characters of messages sent between Hitler and his generals.’

‘After the war, equipment was either spirited away by security services, or destroyed on orders of Churchill. The importance of Colossus was only realised in 1996, following publication of secret documents by the US. As a result, authorities grudgingly allowed a Colossus to be rebuilt at Bletchley Museum.’

‘As far as the rest of my army experience was concerned, I spent two years at Kedleston Hall, which included some exciting times around D Day when traffic was extremely heavy. Then, some of us were posted to Harrogate. Whilst there, my husband-to-be, Ed, came back to the UK, so I was allowed 48 hours leave just after Christmas 1944.’

‘We married in March 1945, and he got a posting in Birmingham, but I returned to Harrogate. Of course, after VE Day, we were all out of a job, as there was no more German traffic. I was demobbed in July 1945, just as Ed was sent to Germany with the Army of Occupation.’

Marj and Ed eventually moved to Australia, where Marj was an active member of the community until her retirement: ‘I was a member of Probus, Red Cross; I did Meals on Wheels for 30 years,’ she says.

In 2016, Marj was awarded the medal of the Order of Australia for her service to the community and the church.

Starting out as a volunteer at Resthaven Port Elliot, Marj came for a respite stay in February 2020, before moving in at the end of May.

‘We’d been looking for a retirement home, and, working for the church, when it opened, I just thought it would be a good place.’

‘Are they looking after me? Yes indeed.’

‘I do a lot of the activities, I like the quiz, and the carpet bowls, the bocce, anything that’s going, really.’

‘I’d heard of Resthaven, I knew it would be a good place to be.’

Thank you for sharing your story, Marj!

Celebrating 85 years in 2020, Resthaven Incorporated is a not for profit, South Australian aged care community service associated with the Uniting Church. Resthaven’s residential and in-home care and support options are offered throughout metropolitan Adelaide, the Adelaide Hills, Murraylands, Riverland, Barossa, Fleurieu Peninsula and the Limestone Coast.